Engaging with the Past: June Meeting

A small selection of the regular reading group (and one newbie – Padmini Broomfield – freelance oral historian and heritage consultant) who weren’t otherwise on holiday, met in June to discuss Graphic Novels. The topic was suggested by Katy Ball (Portsmouth City Museum) after she came across an interesting Manga book commissioned by the British Museum; Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure by Hoshino Yukinobu.

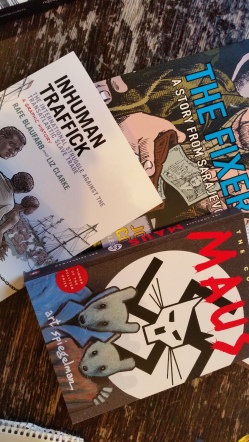

It was noteworthy that most of the graphic novels we discussed (which were by and large, bestsellers) dealt with difficult histories; The Holocaust, war, slavery. Is there something about the medium that lends itself to broaching subjects which are largely considered ‘unrepresentable’ in one way or another? About the space between storyteller and artist that the author(s) takes? Or, perhaps, the possibility for multiple narratives? Whilst there is an intertextuality of words and images, some pages have no text at all, the reader interprets images, or a single image – does this allow the ‘space’ difficult and traumatic histories perhaps need in their representation? Or is this more closely connected to autobiography? To the life and family experiences of authors like Spiegelman and Sacco? Or – more cynically – are these subjects which will mean the genre is taken more ‘seriously’? We considered criticisms of the the abundance of historic Holocaust imagery, is the metaphor in Maus a way to re-imagine The Holocaust in a new way?

Are non-fiction texts still ‘Graphic Novels’? The Inhuman Traffick text we considered is described by the authors as a Graphic History. The text deals with the transatlantic slave trade but, interestingly, is as much a book about doing history as representing it. There are primary documents and guides at the back, making the text a sort of graphic-novel-history-comic-textbook-source-book. The use of image as story also teaches important skills in analysis on its own. The ‘story’ in Inhuman Traffick ends at the National Archives at Kew, culminating by ‘showing the strings’ of how we do history.

Can graphic novels themselves be thought of as ‘exhibitions’ of a sort? In their arrangement, and the way we ‘read’ them; through their use of juxtaposition and intertextuality? This media relies on the intertextuality of words and images, in much the same way that museum exhibitions do – there seems a natural creative affinity between the two that is worth exploring. As much as the Yukinobu manga engaged with artefacts from the British Museum in its narrative, could museums utilise graphic novels in their own exhibitions, as ways of creating alternative ‘narratives’? Proposals to present research and history projects in graphic novel format have been met with some suspicion and confusion in the past. We were left intrigued by what a museum exhibition as a graphic novel would look like (co-created/curated by an artist already working in this genre), taking on board some of the representational ideas and methods of the graphic novel in arranging and designing an exhibition.

TWITTER RESPONSES / FURTHER READING

@jessicammoody Jonathan Walker wrote a postmodern history book with graphics called Pistols! Treason! Murder! Worth a look.

@jessicammoody Pride of Baghdad also a useful one for reflecting on recent history

@jessicammoody ooh I love Maus and Palestine (Sacco): also Abina and the Important Men, and want to read the Suffragette GN as well.

@jessicammoody They’ve got a bunch of folks who specialise in it at Chichester. Hugo (on TinTin), but also his PhD students

@jessicammoody and yes Persepolis is brilliant. I also like Dykes to Watch Out For but its more of a cultural artefact than history book.

@jessicammoody Ooh, also relevant: I went to a great thing with Davodeau at the Institut Francais. They’re really good for serious BD events

@jessicammoody RT:“@GdnCulturePros: #OpenComics: untold stories – share your comics and graphic art http://dlvr.it/Bf3wdC #arts #culture”

Reading:

Graphic Novels:

- Art Spiegelman, Maus (Penguin 1996)

- Joe Sacco, The Fixer (Drawn & Quarterly, 2003)

- Rafe Blaufarb and Liz Clarke, Inhuman Traffick (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Articles:

- Special Issue of Rethinking History, ‘History in the Graphic Novel’ http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rrhi20/6/3

- Michael Cromer and Penney Clark, “Getting Graphic with the Past: Graphic Novels and the Teaching of History” Theory & Research in Social Education Vol. 35, Iss. 4, 2007

Catherine Fletcher

Catherine Fletcher  Andrew W M Smith

Andrew W M Smith  Charlotte L. Riley

Charlotte L. Riley  Padmíní B

Padmíní B One of York’s many ghost walks

One of York’s many ghost walks

Patch Murphy

Patch Murphy

Engaging with the Past: March Group Meeting

Engaging with the Past: March Group Meeting

David Andress

David Andress  Jessica Moody

Jessica Moody  Kresy-Siberia

Kresy-Siberia  Hilary Davidson

Hilary Davidson  Robert James

Robert James